News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search

Peking University, May 28, 2011: “Remember, this is the Triangle; if you get lost, just here wait for me,” a mother told her little son who visited a campus for the first time.

The boy, motalk, grew up and went to college — Peking University — where his mother works. “My dorm is close to the Triangle — one minute’s walk from the fourth floor. I have been particularly proud to live and to approach history, of which the place is recognized.”

The Triangle (Sanjiao Di, literally a triangular spot), the central point of today’s PKU campus, has witnessed the history of the university and the country for six decades. Because of recent demolition and reconstruction project around the area, the Triangle was temporarily blocked and nearby trees cut down, which made it a spotlight of the public once again.

Less than 10 square meters, the spot was named because of its shape — as a triangular parterre with a 3-way intersection. South of the Peking University Hall, the whole Triangle area is the path people must follow from major living zones to classroom buildings.

Central spot of the Triangle area (before November 2007/File photo)

Fallen poplar near the Triangle, June 5, 2011 (Photo/seegastby)

“New PKU” stepping into a “Triangle” era

Yan Yuan, or today’s PKU campus, belonged to the former Yenching University which was merged into PKU during a nationwide restructuring of colleges and departments in 1952. Before PKU moved from central Beijing’s Shatan, there was no “Triangle” either on the PKU or Yenching campus.

A Yenching map in 1925: "triangle" not found

Behind the move to the new campus was a New PKU of the People’s Republic that intended to mark a break from the old one. The university’s anniversary day was changed to May 4, a revolutionary moment in the May Fourth Movement that foreshadowed the birth of the Chinese Communism.

The Triangle became an ideal terminal of news and information, because of its key location near the Grand Dining Hall where major gatherings took place. The Triangle has played its part in reflecting China's political situations.

Qian Liqun, a renowned scholar and professor at the PKU Department of Chinese Language and Literature, witnessed the history right after he entered PKU in 1955, according to a Southern Weekly report.

In 1956, Chairman Mao Zedong called on the Party and the nation to “let a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend.” Based on this principle, the CPC Central Committee launched a “rectification campaign” in the spring of 1957. With such encouragement, Zhang Yuanxun and Shen Zeyi, two of Qian’s classmates, wrote a poem “It’s the Time” and posted it on a wall of the dining hall on May 19.

In Qian’s memory, “the main battlefield was the Democracy Wall, while the bulletin boards at the Triangle played a supporting role limited by its size.”

It’s the time / to let criticism / patter against my head here; the new-born greens are / never of the sunshine in fear!

My poem / is a torch / that burns all / the mankind’s walls; its flame is never obscured / because the spark comes / from the May Fourth’s calls!

Inspired by the poem (excerpts above), many other PKU students started to write poems and essays and shared them around the Triangle. “Anyone could make a speech in front of the wall and the listeners were free to raise questions or join debates,” Professor Qian recalled.

The “Anti-Rightist Movement” started and “It’s the Time” was defined as a bugle which “agitated people to fight against socialism.” Zhang Yuanxun, among other PKU students and faculty, was consequently silenced and disciplined.

The Triangle had never been as stable as a triangle, especially in the “Cultural Revolution” (May 1966 - October 1976). Nie Yuanzi, Party chief at the Philosophy Department, posted a “dazibao” (poster with big characters, prevalent in China from the 1950s to 1980s) on May 25, 1966 jointly signed by six other staff members. Criticizing Peking University for being controlled by the "revisionists," the “dazibao” on a wall near the Triangle added fuel to the flames of the Maoist mania.

From the end of the “Cultural Revolution” to the late 1980s, the Triangle restored its liberal “tradition” and evolved as a platform for people to freely express their political views.

Xichuan, deputy dean of the School of Humanities at China Central Academy of Fine Arts, was admitted to PKU in 1981. “Then there was only one TV room in every dorm building and few newspapers or magazines, so the Triangle was naturally an irreplaceable part of our campus life,” Xichuan told the Southern Weekly.

In 1980, the government carried out experiments of grass-roots democracy and permitted university students to campaign for “people’s deputy” at the district-level people’s congress. As Qian Liqun recalled, the candidates delivered speeches with reform outlines at the Triangle, answered the voters’ questions, and canvassed. After thinking over, Qian voted for a student who was “the most persuasive, calling for freedom of expression.” This campaign slogan was what most PKU students would buy; therefore, the candidate rowed over, the Southern Weekly reported.

Besides politics, Xichuan was mostly impressed by modern China’s first performance of action art at the Triangle in the mid-1980s. He still remembered that noon when a few young men climbed up to the dining hall next to the Triangle through a ladder, stood behind a wood board, and began to throw their clothes down. They came out in but swimming suits.

The young students were immediately more dumbfounded than the onlookers: unnoticed, the very ladder on which they depended was taken away, Xichuan told the Southern Weekly.

Information center at PKU

After 1990, dramatic changes happened to the Triangle. Video monitor cameras were set up. Despite regular academic event information, the bulletin boards started to be filled with various advertisements about house renting, full- or part-time job hunting, and language training — specifically for those who were eager to study abroad.

Apart from the commercializing trend, a large number of independent student associations still placed their exhibition boards and posters around the Triangle, especially during the “hundred-association battle” when they recruited new members at the very beginning of every semester. Hence, the Triangle gradually faded out from the stage of politics and turned more an information center on campus.

A commercialized Triangle since 1990 (File photos)

Maige (alias), a young teacher at PKU, was admitted to the Chinese department in 1991. Maige said he was attracted by the recruiting posters of Wu-si Literature Society as soon as he arrived at the Triangle. Later, he not only became president of Wu-si Literature Society, but also established his own associations — he went to the Triangle to post posters almost every day. What impressed him most was that purely commercial posters started to compete for space against students’ interests. Maige and his fellows had to take turns to watch for their space at the Triangle. Once they saw someone with a roll of papers and a bucket of paste, they came forth and ask him to leave. Sometimes, even physical conflicts occurred.

Li Zhe (alias), now working for a newspaper in the south, pursued his master’s degree at PKU in 1994. “More students went abroad for further study and the Internet was becoming increasingly popular,” Li remembered. The Triangle, its walls and boards gradually faded out — especially after the former dining hall was rebuilt as today’s PKU Hall. “The political atmosphere, at the Triangle, was less, and less, and less.”

However, less is not none. PKU students after a decade gathered at the Triangle with political appeals — this time, in protest of the US hegemonism. The US-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) force bombed the Chinese embassy in Yugoslavia and killed three journalists in May 1999. PKU students were the first to deliver a letter of protest and set up a memorial hall at the Triangle to mourn the dead. When seeing those young and passionate faces, Professor Qian Liqun, who was 58 then, seemed to see his own youth returned, the Southern Weekly reported.

In memoriam. On May 19, 2000, a freshwoman named Qiu Qingfeng was killed near the PKU Changping Campus. Students organized a candle memorial service at the Triangle — “Everyone present could feel the great significance of the place… a grand power,” Qianfu, a writer who attended the service then, told the JCP News.

The university authorities changed its policy and from academic year 2000-01 all freshpersons no longer had to study at the campus in rural Changping, 38 kilometers from Yan Yuan.

The flourishing age of the Triangle seemed to end in the 21st century. Tian Yu (’05) said only under two circumstances would she go to the Triangle: passing by on the way to the classroom buildings and taking someone to visit PKU.

“Nowadays, it merely has symbolic meanings,” said Tian. “Posters of student associations and information of lectures are published on the BBS. What has left for the Triangle are neither politics nor avant-garde arts in the 1980-90s, but all advertisements about training and renting.”

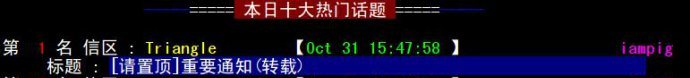

The "Triangle" always tops the list among popular BDWM boards

As China’s leading institution for computer science and information technology research, PKU stepped into an Internet age in the 1990s. The Triangle, however, was not forgotten: a PKU-based YTHT.net, the country’s top independent BBS site from 1999 to September 13, 2004, saw its “Triangle” board with the largest number of traffic and posts. The “Triangle” board of BDWM, now official bulletin board service of Peking University, is almost an online version of the good-old Triangle on campus, and more than that — full of news, information, discussion, debate, and surveillance.

Death of the legend?

Among the BDWM users was motalk. He posted, posted at the “Triangle” board, and his posts elsewhere were sometimes copied to the board.

“I got up early in the morning to post a poster at the Triangle to promote a lecture… I spent several minutes but failed to find a place: I suddenly realized all the shelves and bulletin boards at the Triangle were gone!” the copied post read.

“Later I heard that the Triangle was going to be ‘put in order,' and even later I knew that the university was to be 'evaluated.’”

On the morning of November 4, 2007 at the Triangle, two electric welders were fixing steel bars to the triangle-shaped lawn, while the electronic wall of the PKU Hall in the north was telling the date — 278 days before the 2008 Beijing Olympics. In the dust and flare, students came and went.

It was on October 31 that the decade-old bulletin boards at the Triangle were torn down. A Student Union spokesperson claimed that more and more commercial advertisements had turned the bulletin board not a preferred place for useful information communications anymore, and disaccorded with the environment of PKU. “Therefore we suggest it be torn down.”

The most direct drive would rather be the Ministry of Education’s nationwide “higher education evaluation.” A 5-year-a-round mechanism was pronounced by the ministry in 2003, and four years later, the university that used to refuse the “evaluation” took the initiative to demolish the trouble-making bulletin boards. “Gone is the day when the university could say ‘government grants left here, official documents taken away,’” the Southern Weekly reported.

This issue aroused controversy at PKU and even in the whole society. People were recalling and memorizing the Triangle and online comments filled the Internet.

Some supported the tearing down of the bulletin board. Xing Taotao, a philosophy professor who was admitted to PKU in 1981, thought it not something regretful, because the nature of the Triangle had changed and it wasn’t the original Triangle anymore, Beijing Times reported.

A ’09 undergraduate from the College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering described the bulletin boards as too old and full of ads about renting houses and training courses. He said there was little useful information for students and it should have been removed a long time ago, according to the Beijing Youth Daily.

Because of the 2008 Olympics, the place should be “regulated,” said then PKU President Xu Zhihong during an interview with the Beijing Youth Daily. “But it should not be called ‘demolition.’”

President Xu's opinion was echoed by university spokesman Zhao Weimin. "The bulletin boards were plastered with commercial advertisements, and the Triangle doesn't function any more as a platform for exchanges of academic opinions because the online bulletin board service is widely used by students," according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post (SCMP) on November 3, 2007.

Zhao said the demolition had nothing to do with the ministry's visit later that month: "There's no need to make the issue political or link it to the assessment by the Ministry of Education."

But according to a Southern Metropolis Daily report, the PKU Security Department later confirmed that the "regulation" was related to the evaluation as "the campus appearance will be assessed as well."

Others opposed the “regulation” or “demolition.” An alumnus named Liu Xin (’04) expressed his disappointment and sorrow. “What impressed me most at the Triangle were those posters disclosing bad manners in the cafeterias or the dormitories and the ones publicizing different student associations. Although the Triangle’s function of information and communication can be replaced by modernized ways, emotionally, I feel frustrated.” A student from the School of Foreign Languages said as an information center for a long time, the Triangle had a cultural meaning to PKUers and it was part of the PKU spirits, which should be reserved.

"The divergent opinions expressed on the boards underpinned Peking University's reputation as an institution tolerant of different ideas," the SCMP report commented.

Triangle today

Recently, the Triangle was temporarily blocked because of the reconstruction of No. 16 - 18 buildings. When asked about the influences on the student associations, a member of one of the associations told the Beijing Youth Daily, “Actually, there aren’t obvious impacts, because these days we publicize and exhibit our association through lots of other ways."

"In fact, the Triangle's figurative meaning has already exceeded its actual one,” the student added.

With 2-sided bulletin boards, the Triangle was more recognized, however, by another side for movable posters — usually self-made by students, before November 2007.

Student hand-drawn posters (File photo)

Today's PVC painting with truss at the Triangle

All the three sides have been torn down and cleaned up. Ever since, few hand-drawn posters could be found on campus. “It’s a pity for this artistic tradition at PKU,” said Le Le ’13 from the Law School.

The Triangle still remains geographically. Its symbolic significance regarding the PKU spirit has been considered immortal, as “such a public sphere represents the soul of a university,” the Southern Weekly reported on November 8, 2007.

Even for adult students, the "symbolism," "immortal value," or "soul" topic seemed too loaded; between a child and his mother the Triangle but “links” — “that’s always deep in my memory,” wrote motalk.

“But where should I go if I get lost now?”

Extended Reading:

Reported by: Xu Xinyi and Jacques

Edited by: Jacques