News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search

A special edition of PKU News in commemorating the 113th anniversary of Peking University.

Peking University, Apr. 29, 2011: "In view of your learning and your long residence of 40 years at our capital, besides 15 years in other parts of China, you are regarded by us with profound respect. When we hear your words we ponder them and treasure them up as things not to be forgotten. It is by your scholarship and your personality that you have been able to associate with the officers and scholars of the Central Empire in harmony like this,” wrote a senior Chinese official in a letter to an American missionary.

The missionary was the first President of Jingshi Daxuetang (Imperial University of Peking), China's first modern national university and precursor of PKU; The fact, however, has been for a long time ignored in the official PKU history.

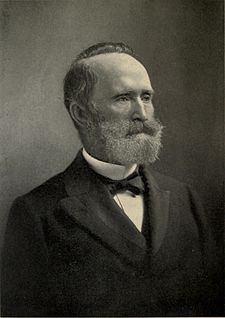

With the Chinese name Ding Weiliang, William Alexander Parsons Martin (1827-1916) was a significant figure in the last years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

A Portrait of W. A. P. Martin

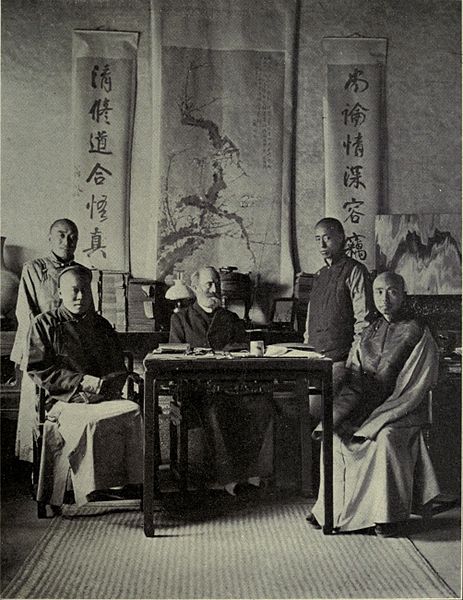

W. A. P. Martin with his Chinese students (File photos)

Born in a Presbyterian family in Indiana, Martin made his mind to study theology and came to China as a missionary in the 1850s. Because of cultural and linguistic obstacles in spreading Christianity, he started to learn Chinese and read through Chinese classics such as Shangshu, The Analects, Book of Changes, and Book of Songs, and thus became an old China hand.

Due to his deep and broad knowledge of Chinese culture, Martin was recommended in 1865 by Anson Burlingame (Pu Anchen), the American diplomatic minister to China, and Thomas F. Wade (Wei Tuoma), the British diplomat, as the third president (Zongjiaoxi) of Jingshi Tongwenguan (Tungwen College, or the School of Combined Learning), the first government school for teaching Western languages in late Qing Dynasty.

Launched in 1862, Tongwenguan only offered language courses at first, and Martin fundamentally reformed it. He implemented new teaching programs for the school, and added scientific courses such as physiology, medicine, and astronomy, transforming Tongwenguan into a modern, comprehensive school. He organized the compilation and translation of new textbooks for courses that were offered for the first time in China. He encouraged, engaged renowned foreign and Chinese scholars to join the faculty. With his efforts, Tongwenguan has set up a modern, Western system of teaching and management, turning out a generation of Chinese translators and diplomats, two of who became Emperor Guangxu's English teachers.

In 1898, the Imperial University of Peking was established as the reform movement, later known as the Hundred Days’ Reform proceeded. Martin again was appointed President (Xixue zongjiaoxi, or general educator for Western learning) by Emperor Guangxu on August 9.

"As [the prospective students, mainly mandarins] of the Shixueguan (official-training college) have gone through the imperial civil service system, they are already competent in Chinese learning (Zhongxue); They attend the university specifically to study the Western lore," Education Minister Sun Jianai's memorial to the emperor read.

Sun, then minister of personnel, served as "guanli daxuetang shiwu dachen" (guanxue dachen), combining the roles of the (education) minister for the new imperial university's affairs, "recteur" in the French system, and non-resident "university chancellor" in the UK system.

In his book The siege in Peking, China against the World: By an eye witness, Martin styled the post in English as "high commissioner for education," and called the minister for Tongwenguan affairs "director."

Together with Minister Sun, Li Hongzhang, a leading statesman, had recommended Martin for the presidency. Sun's report to the throne was ratified on the day of the appointment.

Earlier on July 17, Sun suggested that Xu Jingcheng, vice minister of works, be appointed Zongjiaoxi (general educator, or President), and Sun himself temporarily fill the position before Xu assume the presidency. However, as Xu was sent abroad to deal with Russian affairs, he never took office; There was no edict authorizing this report either. Martin, the de jure President since August 9, was the head administrator ipso facto.

Zongjiaoxi's duty is similar to Jijiu (literally "libation-pourer") or Siye ("service handler," or assistant jijiu) at Guozijian, according to the 1898 Charter of the Imperial University of Peking drafted by Liang Qichao.

Jijiu was the chief executive at the imperial academy – sometimes considered (but not officially recognized) a forerunner of Peking University based on their shared tradition as China's national central institute of learning.

"Real power belongs but to (Zongjiaoxi) W. A. P. Martin," recalled Luo Dunrong, a former Imperial University Press editor, in his "Record of the establishment of the Imperial University of Peking" (Jingshi Daxuetang chengli ji) published in 1912.

In the July 3 edict that authorized the imperial university's implementation, Emperor Guangxu pointed out that Zongjiaoxi "should be selected among those scholars versed in both Chinese and foreign lore."

In the August 9 memorial, Minister Sun Jianai further reported:

The previous memorial (on July 3) noted Zhong zongjiaoxi instead of Xi zongjiaoxi. Its original purpose was to have Zhongxue (Chinese learning) dominate Xixue (Western learning). But in this case, if Western teachers thus hired are not that learned, it does no good to our talented students; if otherwise, they are unwilling to be belittled. Ding Weiliang (W. A. P. Martin), for example, has served as Zongjiaoxi at Zongli Yamen for years; if appointed fenjiaoxi (middle-level teacher), he would refuse. I propose to assign Ding Weiliang to the post Zongjiaoxi, in charge of Western learning, and I will make it clear to him his due powers and responsibilities, beyond which he will not bother to care.

Sun also reported that the received, competitive salary standard for high-quality Zongjiaoxi was 600 taels per month; But in Martin's opinion, he would accept the post with just the same amount as Tongwenguan President, or 500 taels, "having stayed in China for a long time and eager for its rejuvenation."

Xu Jingcheng later served as acting education minister from July 1899 to July 1900 before being executed for objecting to Empress Dowager Cixi's rule to attack foreigners in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion – a period of extreme social unrest that has led to the suspension of the imperial university till 1902 (Tongwenguan was merged into it in the same year).

Xu's case was redressed in 1901, as was demanded by the Eight-Nation Alliance in the Xinchou Treaty (Boxer Protocol): "Imperial Edict of the 13th February last rehabilitated the memories of ... Xu Jingcheng ..., who had been put to death for having protested against the outrageous breaches of international law of last year."

Sun Jianai

Xu Jingcheng

Zhang Baixi

President Martin with Imperial University of Peking faculty members (File photos)

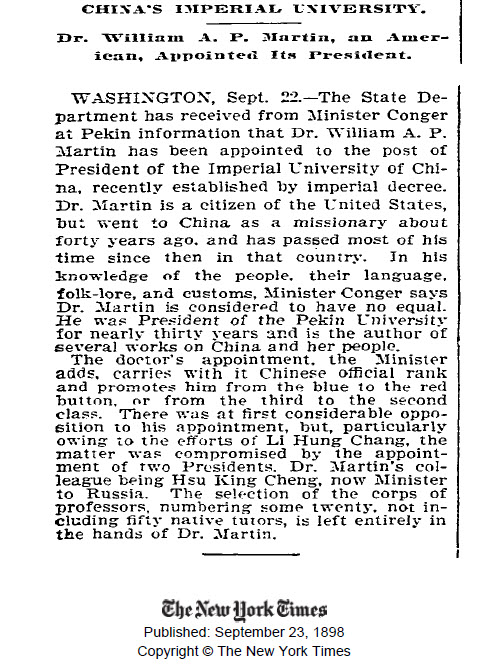

On September 22, 1898, the New York Times covered Martin's new post at the university titled “China's Imperial University. Dr. William A. P. Martin, an American, Appointed Its President.”

However, President Martin was unrecognized and even traceless in the official PKU history. He was an interpreter on behalf of the US during the negotiation of Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin), and thus was vulnerable to be regarded as an accomplice of "imperialists." Because he witnessed the Beijing massacre targeting foreign ministers and civilians, he was hostile to the Boxer Rebels and severely criticized them as being “barbarous.” His contributions have begun to be excluded from official records since, particularly after the founding of New China.

The People's Daily, mouthpiece of the Communist Party of China, ran nine articles that mentioned Martin from 1949 to 2000, in which eight labeled him "imperialist," "invader," or "intimidating missionary."

When the Eight-Nation allied forces occupied Beijing, rumors have it that he was involved in joining their looting and pillage of the capital — although it was falsified. Also, he picked Hainan Island for the US to take, if possible, "in lieu of the payment" of the Boxer Indemnity in his book The siege in Peking. He once suggested the occupying troops overthrow the Manchu government's rule and banish Empress Dowager Cixi. The Second-Class Mandarin Martin was consequently less trusted by the Qing court after the turmoil.

On September 20, 1901, President Martin reported to Prince Qing on the dispatch of a new education minister to restore the university, as peace had been resumed since the signing of the Boxer Protocol on September 7. He received a reply: the request would be submitted "after the Imperial Highness' return."

President Martin, along with other Western faculty members, was dismissed due to "financial difficulties" in 1902 soon after the university's restoration. The education minister then was Zhang Baixi, appointed on January 10, 1902.

The New York Times reported on March 23, 1902 titled "New President of Peking University":

The Dowager Empress has appointed Wua-Mu-Lun [sic] to be President of the Imperial University, to succeed the Rev. W. A. P. Martin, who was recently relieved of the Presidency of the institution. Wua is a progressive and learned official.

The new President (Zongjiaoxi) Wua-Mu-Lun (Wu Rulun, 1840-1903) was appointed by Empress Dowager Cixi, the Qing court's de facto boss, who brutally suppressed the emperor's reform endeavor in 1898, whose capricious decisions during the Boxer Rebellion exacerbated the national, international crisis.

Under Martin's presidency, the university, later known as the 1898 Imperial University (Wuxu Nian Daxuetang, in comparison with the "1902 university") produced no graduates due to the social chaos in 1898, 1899 to 1902. Martin and his team's effort, however, did lay a foundation for its future resplendence that is comparable to its prestige since inception.

Earlier on February 8, 1902, the American newspaper reported the rumors that the Chinese government had dismissed all the European professors from the Imperial University, while "[t]he President, Mr. Martin, has been offered a subordinate position."

"[E]lementary schools are more needed," the "Chinese Directors" were quoted as saying.

That and "financial difficulties" are only excuses, argued PKU historian Guo Weidong; The growing nationalist sentiment then, and renowned scholar Yan Fu's "selfish motives" and efforts to replace President Martin, contributed to the authorities' determination to dismiss the entire Western faculty on February 16.

The decision also symbolizes the end of the historic period when national education institutions were in the charge of Western missionaries, Guo added.

Yan Fu, however, was exalted to the position of the Imperial University head only in 1912, and then the first President of the Government University of Peking (Beijing Daxuexiao).

Despite the dramatic denouement of Martin's career at the university, he has not only contributed to China's modern education, but also enhanced mutual communication between China and the rest of the world.

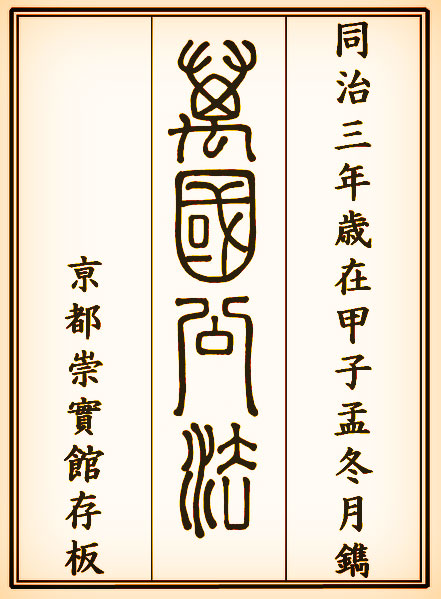

He was the first who translated Henry Wheaton's Elements of International Law into Chinese, "Wanguo Gongfa," an enlightening work for both Chinese scholars, mandarins – and their counterparts (or future foes) in Japan.

Elements of International Law, translated by W. A. P. Martin, first published in 1864 (File photo)

Martin's books such as The Lore of Cathay or the Intellect of China (1901), A cycle of Cathay; or, China, south and north, with personal reminiscences, and The Awakening of China introduced China to the rest of the world. In the latter he recorded the letter with which this article opens, written in 1905 by the director of the Normal College for the Two Lake Provinces, where liberal-minded Viceroy Zhang Zhidong once reigned.

It is also in the book that Martin, with his deep understanding of Chinese culture and Chinese people, prophesied against that disordered, backward, and hard age that “Animated by sound science and true religion, it will not be many generations before the Chinese people will take their place among the leading nations of the earth.”

The Awakening of China, written by W. A. P. Martin (File photo)

In 1902, just after Martin's leaving from the Imperial University, Viceroy Zhang Zhidong engaged him to assume the office of president of the proposed university in Wuchang, Hubei Province – where republican revolution broke out in but nine years. The university failed to materialize.

Zhang also asked Martin to act as his legal and political adviser. The duty was later changed into instructing his junior mandarins in international law because the central government declined to allow any foreigner to hold the post of adviser.

Martin commented in his 1906 book The Awakening of China:

The objection was represented as resting on general policy, not on personal grounds. If, however, the Peking officials had read my book on the Siege, in which I denounce the treachery of Manchu government and favour the position of China, it is quite conceivable that their objection might have a tinge of personality.

On December 18, 1916, after living in China for 62 years, W. A. P. Martin passed away in Beijing. Insomuch as his contribution to the country and the people, he was praised as “Taishan Beidou” (very eminent and respectable) by Li Yuanhong, then President of the Republic of China.

Obituary on New York Times on December 24, 1916 (File photo)

W. A. P. Martin once recalled his relation with Peking University in his The Awakening of China:

In 1898 the young Emperor, taught by defeat at the hands of the Japanese, resolved on a thorough reform in the system of national education. It would never do to confine the knowledge of Western science to a handful of interpreters and attachés. The highest scholars of the Empire must be allowed access to the fountain of national strength. A university was created with a capital of five million taels, and the writer was made president by an imperial decree which conferred on him the highest but one of the nine grades of the mandarinate.

Two or three hundred students were enrolled, among whom were bachelors, masters, and doctors of the civil service examinations. It was launched with a favouring breeze; but the wind changed with the coup d'état of the Empress Dowager, and two years later the university went down in the Boxer cyclone. A professor, a tutor, and a student lost their lives. How the cause of educational reform rose stronger after the storm, I relate in a special chapter. It is a far cry from a university for the élite to that elaborate system of national education which is destined to plant its schools in every town and hamlet in the Empire. The new education was in fact still regarded with suspicion by the honour men of the old system. They looked on it, as they did on the railway, as a source of danger, a perilous experiment. (pp. 210-11)

A chronology of Martin’s life

1827: Born in Indiana, the United States

1846: Graduated from Indiana University

1850: Arrived in Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

1858: Served as interpreter for US minister in negotiating the Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin)

1959: Traveled to Beijing and Japan

1863-68: Worked in Beijing

1869-95: Served as President of Tongwenguan in Beijing

1898-1902: Served as President of the Imperial University of Peking; relieved in 1902

1916: Died in Beijing

Martin edited the Peking Scientific Magazine, printed in Chinese from 1875 till 1878, and also published in the Chinese language:

Evidences of Christianity (1855; 10th ed., 1885)

The Three Principles (1856)

Religious Allegories (1857)

(tr. into Chinese) Elements of International Law by Henry Wheaton (1864)

An educational treatise on Natural Philosophy (1866)

(tr. into Chinese) Introduction to the Study of International Law by Theodore D. Woolsey (1875)

(tr. into Chinese) Guide Diplomatique by Georg F. von Martens (1876)

(tr. into Chinese) Das moderne Voelkerrecht by Johann K. Bluntschli (1879), translated from Charles Lardy's Le Driot international codifié

Mathematical Physics (1885)

(tr. into Chinese) Treatise on International Law by W. E. Hall (1903)

Martin also published in English:

The Chinese: their Education, Philosophy, and Letters (1880)

A cycle of Cathay; or, China, south and north, with personal reminiscences (1896)

The Siege in Peking, China against the World: By an eye witness (1900)

The Lore of Cathay or the Intellect of China (1901)

The Jewish Monument at Kaifungfu (1906)

The Awakening of China (1906)

References:

Shen Hong. "Ding Weiliang: Ruhe pingjia ta zai Beida xiaoshi zhongde diwei" (W. A. P. Martin - how to evaluate his role in PKU history). Kua-wenhua Duihua (Cross-cultural Dialogue) Vol. 8 (March 2003). Shanghai: Shanghai Wenhua, pp. 94-109.

Peking University and the First Historical Archives of China. Jingshi Daxuetang Dang'an Xuanbian (Selected Archives of the Imperial University of Peking). Beijing: Peking University Press, 2001.

Extended Reading:

【Anniversary Special】Anthems across a century

【Anniversary Special】PKU Anniversary Day: Questions and the answer

【Anniversary Speical】How to "identify" PKU

【Anniversary Special】"In the beginning was the word"

Written by: Cao Yixing

Edited by: Chen Miaojuan and Jacques