News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search

Peking University, Beijing, May 14, 2010: For Robert Frost, home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

Hu Shi is, again, back home.

On May 24, Stephen Owen, a prominent expert on China studies and professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University, will inaugurate the "Hu Shi Liberal-Arts Lecture Series" initiated by the PKU Department of Chinese Language and Literature with a speech on "Happiness, Ownership, Naming: Reflections on Northern Song Cultural History." The opening lecture is scheduled at 15:00 in the Sunshine Hall of the PKU Yingjie Overseas Exchange Center.

Stephen Owen (Yuwen Suo'an)

The lecture series is established at the centennial commemoration of the Chinese Department of PKU, and the semi-annual event will invite one lecturer from overseas and one from China respectively, the Southern Weekend reported Thursday.

It is the first time in more than 60 years when an academic event at PKU is entitled "Hu Shi," one of the leading figures during China's New Culture Movement (1915-1920s) and President (1946-1948) of the then National Peking University.

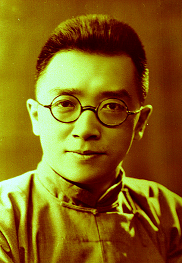

Hu Shi (1891-1962)

Born in 1891, Hu Shi (or Hu Shih, courtesy name: Shizhi) had won a scholarship appropriated from the "Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Scholarship Program" and went to the US in 1910. He returned to China in 1917 after completion of his doctoral dissertation under John Dewey, philosopher and professor at Columbia University.

As he joined the faculty of PKU at the invitation of President Cai Yuanpei and lectured at departments of Chinese, English, and Philosophy, he received support from Chen Duxiu, dean of the liberal-arts division and editor of the influential journal New Youth, quickly gaining much attention and influence. Hu soon became one of the leading intellectuals during the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Movement, which bred the great spirit of patriotism, progress, democracy, and science, now core values of Peking University.

A propagator of American pragmatic methodology as well as the foremost political liberal in China's Republican period (1912-1949), he always advocated building a new country not through political revolution but through mass education, which was not in line with upsurging movements at that time. One example is when in July 1919, he challenged the activists in an article “More Study of Problems, Less Talk of ‘Isms.'” Deeply convinced of the feasibility of the experimentalist approach, with its reliance on coolness and reflective deliberation, he counseled gradualism and the individual solution of individual problems with "bold hypothesis, but careful verification."

One of his most significant contributions was the promotion of baihua, or vernacular Chinese in literature to replace Classical Chinese, which ideally made it easier for the ordinary person to read.

Hu served as China's ambassador to the US between 1938 and 1942, when China was in war against Japanese aggression.

By the end of 1948, he had decided to quit the position of PKU President and head for the US. In the 1950s, he went back to Taiwan to assume the presidency of the Academia Sinica, while he was also chief executive of the Free China Journal which was eventually shut down for criticizing Chiang Kai-shek.

He passed away and his body was buried, draped with the Peking University Banner. No media coverage on the Chinese mainland was found upon his death in 1962.

Earlier in the 1950s, the animadversion against Hu Shi was widespread on the mainland, because of the highly institutionalized system of ideology and an anti-US propaganda around the Korean War, according to Geng Yunzhi, Academic Committee Member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS).

Hu Ming, researcher at CASS and one of the juniors of Hu Shi's clan, remembered the sensitiveness of Hu from 1949 to the 1980s. The only positive image that he still recollected was a photo of Dr. Hu at the Red Mansion of PKU taken from an in-production movie "Life of Lu Xun," which was immediately banned before its shooting started.

The name of Hu Shi stayed in disrepute even after the "Cultural Revolution" (1966-1976) on the mainland, until 1986 when a top leader pointed out that Hu was "indeed devoted to China's modernization," according to Hu Ming. His manuscript on research of Shuijing Zhu, or Commentary on the Waterways Classic, was published on the mainland in the same year. Academic research on Hu and Dr. Sun Yat-sen has been resumed and justified since then - in officially-censored versions of middle-school textbooks of history, Hu is therefore recorded as an "advocator of vernacular Chinese, thus a promoter the New Culture Movement."

In 1991, a meeting to commemorate Hu's centennial was held in his hometown, Jixi county in East China's Anhui province, under the arrangement of Geng Yunzhi. That was the first of this kind ever on the mainland in decades.

However, Hu is almost nowhere to be found at his university. Even when Li Ao, a renowned independent writer from Taiwan who was jailed by Kuomintang in the 1970-80s, made a speech at PKU and prompted to donate RMB 350 000 for a statue of Hu at campus, the proposal ended without any result. When the Beijing Memorial Hall of New Culture Movement re-opened in 2002, Hu Shi was still, and the only one absent in the relievo honoring vanguards of the significant event that has shaped China's development in the 20th century.

As historian Tang Degang - Hu's student - recalled, Hu Shi was just a real person in life, instead of an "immortal giant," an "evil," or a "bourgeois hedonist" as was once criticized on the mainland. He led a plain life and often took buses with passengers squashed up against each other when lecturing in the US, where one of his few "leisure" activities was merely playing cards or Mahjong.

On leaving PKU in 1948, he urged that for a world-class university, academic independence and academic freedom were more significant than government support in finance and personnel. He never gave up his liberal ideal, and he decided to donate 102 boxes of his book collection remaining in Beijing to Peking University in his last will, according to the Southern Weekend report.

The second article of his testamentary disposition goes: “Confident that academic freedom will one day be restored to Peking University in Peiping, China, I give and bequeath to that University all my books and papers contained in one hundred and two boxes which were left at the University library for safe-keeping when I was obliged to depart from Peiping in December 1948."

Huang Nubo, alumnus of the PKU Chinese department and president of Zhongkun Group, donated RMB 2mn to the department for its centennial including the launch of the Hu Shi liberal arts lecture series.

Prof. Chen Pingyuan, Dean of the Chinese department, commented that it was better for the China studies to be domestically supported, than using "foreign" funds such as the "Boxer Rebellion Indemnity."

The first event in May 2010 also includes Prof. Owen's speeches on "The Magistrate of Peach Blossom Spring," "An Account of Missing Rocks," “'All Mine!,'” and "Echoes: Reading" at the Chinese Department.

About the Speaker:

Stephen Owen (Chinese name: 宇文所安 Yuwen Suo'an) is James Bryant Conant University Professor and professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University.

Prof. Owen's primary areas of research interest are premodern Chinese literature, lyric poetry, and comparative poetics. Much of his previous work has focused on the middle period of Chinese Literature (200-1200); however, he is currently engaged in writing a collection of essays on Chinese literature of the early period. He has a concurrent interest in Chinese drama of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His most recent books have been: An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (Norton 1996), The End of the Chinese "Middle Ages" (Stanford, 1996), Readings in Chinese Literary Thought (Harvard, 1992), Mi-lou: Poetry and the Labyrinth of Desire (Harvard, 1989), Remembrances: The Experience of the Past in Classical Chinese Literature (Harvard, 1986), and Traditional Chinese Poetry and Poetics (Wisconsin, 1985). Three earlier books on Chinese poetry were published by Yale.

Prof. Owen's wife, Tian Xiaofei (pen-name: 宇文秋水 Yuwen Qiushui), is professor at the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University. She entered the PKU English Department in 1985, at the age of only 13.

Extended Reading:

PKU News (Chinese): Steven Owen Speaks at Hu Shi Liberal Arts Lecture Series

Edited by: Jacques

Source: Office of International Relations

Copyright 2010 Peking University News | BeidaNews@pku.edu.cn